You may have thought, and rightly so, where could he go after developing the scrapple empanada?

But no! The cross cultural fusion blasphemy is never finished.

So, it came to pass in the 13th year of our Ford, also known as 2018, that the Dominguez family decided to cruise again.

To make it a little more of an adventure and save some myrhh, three unwise magi decide to board a train in Newark and head to Miami, planning to arrive at six the next evening. I cut my thumb unloading the bags at Penn Station, putting me in a foul humor as our journey begins.

The Christmas decorations adorn the cities as we roll down, and it’s cheery enough but the train stops repeatedly and

thirty-six hours later I’m not in any more of a holiday mood as we approach our penultimate stop six hours behind schedule. The conductor then says it is time for a mandatory monthly engine test that must be conducted before midnight and will delay us another 45 minutes.

We get off, call an Uber and check into a hotel near the cruise terminal.

I doze off as the TV news talks about Syria, the wall and a looming government shutdown.

I dream I’m in Civil War Spain, in a cold mountain village and the only people who come visit are there to take our food, young men as soldiers, or to arrest and execute someone suspected of opposing fascism. And I hear a voice callling “No, no, no. Alex…. Alex…. no, no, no.”

The voice sounds like my aging father, and I think that was his childhood, not mine.

I go back to sleep. I dream I am old and alone except for a cranky bird. And I hear

a voice callling “No, no, no. Alex…. Alex…. no, no, no.”

And I looked up and see…..

Is it Ebeneezer Cruise?

And then he says…

“Can you help me get my shirt on?”

Now, that I’ve been visited by the ghost of Christmas Cruise, I’ll change!

“This is the corn chip of the everlasting covenant,” I say, pulling the perfectly circular blue corn chip from the plate of nopal salad and hold it up before splitting it like the priest had done at mass a few nights earlier.

A few dozen attended the mass

in the ornate baroque cathedral. Catholicism isn’t what it once was here, but everyone needs something to believe in. And I believe Oxxo will never run out of chips and drinks as long as we tithe regularly at the temple of consumerism that never closes.

Aside from the chips, food in Puebla wasn’t quite what I expected.

There are tacos everywhere, but pumpkin seeds, walnuts, mole and sandwiches called cemitas also dominate.

Cemitas are mostly larger than I can finish comfortably. The milanesa variety is the most popular, primarily a breaded chicken cutlet but also made from thinly pounded pork. Others include ham and pata de res, stewed beef tendon from the hoof area, cut into gleaming gelatinous chunks dressed with pickled onion, pepper, carrots and bay leaf. The sandwich was served on a crunchy sesame roll with hand-shredded fresh cheese, avocado and a smoky chili salsa.

A large public market a few blocks past the Lucha Libre arena has people lined up at lunch for the 35 peso ($1.75) treat.

They also sell rapidly outside the arena, along with the Mexico version of shwarma, tacos al arabe, thin sliced beef piled onto a rotating vertical spit topped with a pineapple. Inside the arena, vendors purvey everything from beer to donuts and boiled shrimp, which are carried around in a huge reed basket lined with palm fronds. Meanwhile, fans known as Rudos screamed “Puto!” and other insults at the wrestlers and fans on the other side known as “Technicos.”

They currently have plenty to scream about with drug cartel violence rising and political candidates being killed by the dozen. An outsider president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, known as

AMLO, is elected the day I arrive. That marks my second trip this year coinciding with regime change. Raul Castro retired when I was in Cuba this spring. The timing prompts quips I am a Spanish secret agent.

“Nothing could be further from the truth,” I respond and they nod in agreement (fools!).

On the streets, people are hopeful, at least that they have a sympathetic ear at the top.

“He’s promised a lot,” one driver tells me. “Let’s see what he can get done.”

Once again, we head off to eat.

For those seeking a sit-down meal, many restaurants hawk chili nogado, a stuffed chili topped with a creamy walnut sauce and pomegranate seeds. The stuffing usually contains meat, raisins, pumpkin seeds and other items that ends up being slightly sweet.

Another night, we head to the pasita bar and see a 7-11 across the street, keeping the faithful supplied.

“I hope there isn’t any sectarian violence among Oxxo and 7-11 customers,” I note, and Mike nods, acknowledging my newfound faith.

Apparently, pasita is a raisin liquor, the name derived from the Spanish word for raisin, pasa or la uva pasa, the grape that has passed.

A sign tells us pasita is a must have aperitif. The 30 peso shot comes with a toothpick skewer holding a chunk of fresh cheese and a raisin. It’s sweet but the slightly salty cheese cuts through that a bit and the alcohol does stimulate my appetite, helping revive me from the near coma the cemita induced at lunch.

So, it’s time to decide where to eat another meal.

There’s good food at all price levels. Meals at white tablecloth places can be $25 each including a glass of wine, an espresso and snifter of brandy. One excellent Spanish-Mexican fusion place cured their own jamon from pigs grown nearby.

Snacks, known as botanas, also abound.

They can be as simple as

potato chips in a cup with hot sauce or mayo or both. Or jicama slices with chili powder, nacho chips, shrimp salad, etc. On the cooler end are ice pops known as paletas with flavors ranging from various fruits to

cucumber and chili.

We stop into a place that had been recommended and I give the pipian a whirl. It’s either stewed pork or chicken bathed in a red or green sauce of crushed pumpkin seeds. The green isn’t spicy but has a pleasant herbal, nutty character. Lipika gets arrachera, thin sliced skirt steak, and Mike has chicken tinga, shredded chicken breast in a red chile sauce. A girl tries to sell us a craft beer and the waiter promotes the nogada but we’ve decided otherwise and leave later with half our entrees in doggie bag styrofoam clamshells, thinking we might eat the leftovers the next day. Halfway back to their apartment we run into a woman with a child asking for money and she takes the bag instead when we offer it.

The day before, a guide named Carlos drives us to Cholula, where a Catholic church is built on top of a pyramid shaped temple where children were once sacrificed. Before learning that gruesome history, we stop for lunch at a restaurant with a view of the church, politely declining a free sample of chili-flavored grasshoppers from a vendor outside. I try a little strawberry flavored pulque cactus drink, a syrupy cloudy alcoholic beverage, clear my palate with some beer and order pork with huitlacoche, a type of corn with fungus that surrounds the kernels. The taste is mushroomy and pleasant.

Then it’s a quick trip in tunnels under the temple and a walk around the perimeter where Carlos educates us on the history of the temple and the human sacrifice ritual. Next, he drives us to nearby Tlaxcala, where four indigenous leaders later converted to Catholicism, making the town the cradle of the mestizo culture that eventually developed.

Nearly two thirds of Mexicans have indigenous blood, he tells us.

Conversion took off following the appearance of the Virgin Mary at Guadalupe to a poor Indian. He finally convinced the local bishop when he brought out of season flowers in his tunic, which had the image of the Virgin when he poured them out.

Carlos says the image also contains items the man could not have been aware of if he drew it himself. I ask if that was the key to the conversion.

“The Aztecs didn’t fail because they weren’t strong” Carlos says. “They lost the support of the people.”

We think about this later as I pick the last corn chip from a wicker basket.

“Don’t worry, have faith, there’s more at the convenience store.”

Dear reader:

The first chapter of my account of our recent trek across Cuba has curiously disappeared, so here it is again, with a brief explanation of the journey’s purpose.

As I peruse my account again of the journey across the island by train, I feel I embarked on the adventure a bit like a modern day Don Quixote, full of ideas spawned by competing propaganda, advertising and commercial interests mixed with the mystery of a land locked away for decades, still bubbling with the thoughts of Carpentier, Marti and the like. I hope you can forgive my naïveté and biases and enjoy my tale.

We must find the elusive Yuban people. Apparently, they were an African tribe that escaped from slavery and preserve their culture and music up in the Cuban hills, including the first freeze dried coffee.

It’s an ancient African technique that is lost to time.

They must’ve found a way to do it with Vibranium they brought from Fecunda. (I mean geranium, I don’t want to step on Marvel’s toes.)

The plan is to take a train into the interior after orienting ourselves in Havana for a few days.

The cab from the airport costs 25CUC, pronounced kooks or Seh-Ew-Seh, and short for Cuban Convertible Pesos, which traded one-for-one with the dollar minus a conversion charge of 10-15%. Euros aren’t charged commission.

The cabbie isn’t interested in trading the fare for a 16 gig memory stick, which he says are in demand for listening to music and watching movies but doesn’t need, and

drops us at a building in central Havana that looks war-torn. We enter, adjust our eyes to the light and a voice calls out of the obscurity to us. Sarge points back to the doorway, and a youngish man dressed in a lime green work suit is high up on a ladder painting the wall the same color. He points to a door and tells us to ring the bell for the elevator.

Inside two women are chatting and stop to say they’ll call our Airbnb host after they drop us off on the second floor. Sarge thinks they must live in the elevator from the collection of items around them, a radio that looks like a beer can, a chair, a few snacks.

We wait a few minutes in a hallway looking at the wrought iron cage encasing the entrance to the next door apartment. Once inside the apartment is thoroughly modern, except our host Janet? asks us not to flush toilet paper, because the plumbing clogs easily, and instead put it in the trash, which will be collected each morning.

The next morning, I decide on a paperless poop, and shower after my morning ritual.

Janet hasn’t heard of the Yuban and warns that the train service is slow and unreliable. Undeterred,

we take a cab to the train station, a temporary shed-like building behind a grand station under repair, take a photo of the schedule board, chat with the help desk and walk back amongst areas that range between opulence and complete urban decay. The buildings remind Sarge of his childhood in wartime Beirut.

It’s all very pleasant, though, no one is trying to sell us anything other than a taxi ride, people stroll about, kids play soccer. We stop for refreshment in a luxurious Iberostar hotel, and then later at another hotel to use the internet and eventually pick our way past the crumbling buildings and up the century old stairway to our apartment.

At breakfast, Janet tells us she can fix her apartment but the building is owned by the government and she can’t repair the stairwell or the exterior.

The work so far has been concentrated on the Prado and nearby historic areas where we stopped the night before. Janet said she is waiting to see what happens with the crumbling buildings across the street.

She’s a dentist who rents her home on the side to make ends meet because she earns 50 CUC a month. She doesn’t pay property taxes, health care or student loans, but doesn’t have much leftover for luxuries, if they are available.

Her husband, however, makes more than her renovating apartments and houses. Two years ago, the government allowed sales of private homes. The apartment we’re staying in cost 15,000 CUC. She furnished it with items bought in Venezuela, where she lived for six years as part of an exchange program that traded Venezuelan oil for Cuban medical care under the Chavez regime. The Cuban government waived import duties and shipped the goods for her.

Her sister lives in Canada, and she would like to visit the US if it’s allowed, but is worried about violence there.

“I never saw a gun on the street until I went to Venezuela. Here you can walk anywhere, anytime,” she said.

I don’t feel insecure at all as we walk the streets and I don’t feel any tension when members of various races interact, most likely because everyone is being screwed equally. I tell her, shootings in the US are primarily drug-related or domestic violence cases, but that doesn’t seem to comfort her.

Shopping in Havana is a mix of tourist luxury and Soviet-era empty shelves. One store that purports to be a cheese shop had a few blocks of Gouda, some brick-pack milk boxes and little else. A market whose sign advertised seafood, smoked meats and other items, had a tray of headless catfish on the counter, smoked pork, dehydrated eggs, #10 cans of cabbage and tomato and little else.

A larger department type store had a refrigerated section with frozen ground meats and a few refrigerated cold cuts. Other sections sold appliances, furniture, clothes and various household items.

In the tourist areas, watches, pens, cameras, souvenirs and luxury items are on display. And just down the block, a man is selling strings of onions from a cart and a small shed nearby has makeshift tables with fruit and unrefrigerated meat.

After a few days of padding around, we run into a string of actual stores on Avenida Italia, Calle Italia?, including a supermarket with rows of stocked shelves, including pasta names I recognized, a deli counter and frozen foods. Not a huge selection but well stocked.

It’s hard to shake the bizarro Latin-Lenin feel. Most have known nothing but communism since birth and compared to the US, it’s a mess. However, when you look at other nearby countries; Honduras, El Salvador, even Mexico; Cuba is a safe haven where everyone is educated and fed.

I see a few small fishing boats off the Malecon but no real fish markets in our first two days of stumbling around the old city.

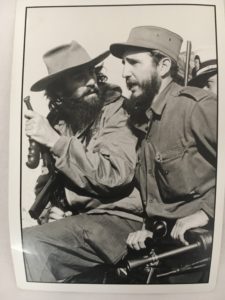

We take a tourist bus out to the plaza where Fidel Castro used to speak for hours, and see the huge metal relief depictions of Che and Camilo Cienfuegos, the personable revolutionary known for his cowboy hat and Tommie gun, who I have decided is the forgotten revolutionary.

Then, it’s a walk to a nearby cemetery, hop back on the bus and stop at a seaside hotel for lunch. The only seafood items on the menu at the poolside bar are fried calamari and a freshwater fish our waitress didn’t seem very enthusiastic about. The waitress says despite being an island Cubans don’t eat much fish. From what I’ve seen so far, seafood is mostly on the menu at tourist hotels, ranging from bacalao, or salted cod, to octopus, shrimp and lobster.

After lunch, we return to our apartment to rest. We drive through the Miramar neighborhood of former mansions that now are the offices of foreign companies and various organizations. We ask where the presidential mansion is and our driver says it’s a huge property with a house not visible from the road. When we ask if Fidel stayed there, the driver tells us no one knew where he lived.

Back at the apartment I flip channels between a Sunday afternoon baseball game and a subtitles showing of a Hulk movie and wonder what the Yuban had for lunch.

The first thing Ernesto says after picking us up at the train station is that Santiago is the heart of Cuba.

A large port and rail terminal meet at the bay, where a distant Colonial fort overlooks the country’s second-oldest city, guarding the channel. (And where I found a postcard of Camilo with Fidel before entering Havana during the revolution)

We later learn the city is the home of the black Madonna. She resides in a church outside of town that is a major pilgrimage site and sits in front of a mountain where escaped slaves fled.

Also known as Ochún, she’s the goddess of love and femininity, dark-skinned and dressed in bright yellow.

Ernesto, still trying to understand our journey, notes all Cubans are white with a little black or black with a little white, before asking

“And why did you take the train?”

Milena, our next Airbnb host, gets the idea.

“Como Che en moto,” she says, referring to his motorcycle trip across South America before meeting Fidel. Yes, it’s a good way to meet the average Cuban, we tell her, adding that I’m more a fan of Camilo, who I think is like Pete?/George Best, the fifth Beatle.

The bathrooms were nothing more than a stinking metal tube extending up from the floor, I tell

Ernesto later during lunch at a restaurant in a patio overlooking the bay.

He says the Chinese are bringing in new trains.

“The problem is the government never has money for maintenance,” Ernesto says. “Look at the rental cars, they’re the cheapest Chinese cars available.”

Our arrival is just in time for a weekly fair with the narrow streets closed to traffic. A live orchestra in the square plays classical music, and Cuban bands are on the side streets, where historic buildings abound, with plaques detailing its history.

In 1801, the rights of the escaped slaves and others were legalized and they were recognized as free men and landowners.

The Royal Order was read before the image of the black Madonna, also known as the Virgin of Charity. That marked Santiago as the first in the island where the freedom of slaves was proclaimed, 80 years before the formal abolition of slavery.

I chat with Milena about our differences, including race and crime and guns in America, telling her most shootings are drug related, and America is fairly safe. School shootings disturb her and while Cuba is poor, she’s glad she can walk outside whenever she wants and feel safe, something I, as a recent stabbing victim, admit I don’t always feel.

She lives in one of the eight or nine houses her grandfather had before the revolution.

A woman who worked for him lived in the house for years and he was able to sell the others before they were taken. However, he lost a store, a bar and parts of a finca, or ranch, where her father still lives and grows coffee as well as some produce.

A truck owned by her grandfather that was used in the revolution now sits in a museum nearby where he is credited with aiding the rebels.

“He really just wanted them to go,” she said of the donation.

Some of her cousins now live in Europe but others stayed. With Castro’s brother Raul retiring this year, everyone is waiting to see what will happen.

“What Cubans really want is for the blockade to be lifted so we can trade more freely with the rest of the world,” she said.

I settle in to the comfortable house, waste a few 1CUC ınternet cards going online because she has a WiFi router and listen to my new favorite station, Radio Reloj, news bits read off while a clock ticks in the background. The station is the voice of the revolution, it seems, constantly informing the populace of developments across the country and the globe, and it hooks me.

After a day of rest, including mass where the priest stops the process to ensure I am a confirmed Catholic before giving me the host, we enlist Ernesto again and head to the mountains.

Ernesto, who drives a small Peugeot, says decades old Wiley’s Jeeps and Toyota Land Cruisers can cost $40,000 because it’s like buying a business. Milena’s husband later says he’s heard of a new car selling for 250,000CUC,

On the way out, we stop to see the

changing of the guard at Fidel’s tomb, which is smaller than Jose Marti’s memorial just to the left, and is marked by a large boulder with a plaque reading Fidel.

Ernesto later agrees Camilo is the forgotten revolutionary but adds outsiders weren’t responsible for his disappearance in a flight to Havana that never arrived.

“He was the most charismatic of all of them,” Ernesto says. “There’s a story that Fidel was speaking once and Raul and Camilo were in back working. When they came out, the crowd cheered so much for Camilo that Fidel had to stop speaking. Fidel was smart and realized that Camilo was more popular and you know what they say, you can’t cast a shadow on Fidel.”

The car winds it’s way up into the mountain to see the Gran Piedra, past guajiros on horseback out cutting brush for firewood. Little piglets suckling on their mother on the way up, strolling down the street on the way back.

The car goes as far as Ernesto is comfortable taking his livelihood, then it’s a

hike up to the top of the big rock. Then down into the little row of houses and stands to see the coffee plantation started by a French planter who escaped Haiti with 25 slaves. Caught in the rain, we stopped for wood-fired coffee and overpaid, 5CUC for coffee and cigar.

And there it was, a little shack, an iron pot over a wood fire, a cloth coffee filter, a few cigars and some carved wood Orishas. All doled out by a few Yuban who have been in these hills for years, now making up prices for foreign tourists like any other Cuban.

A couple stand in the area between two cars for hours as we head to Santiago, their punishment for not buying a ticket. An obviously drunk black man roams the car complaining that his friends can’t sit because they can’t afford the ticket. A pair of police officers speak to him once and when they stop him a second time, we don’t see him again.

I’m really enjoying watching people get on and off at various stops, loading and unloading their luggage and other items from horse drawn carts.

We stop at Camaguey and vendors descend on us, selling a variety of beverages in refilled water bottles as well as sandwiches and cakes.

We get a few 5CUP fried fish sandwiches and a soda. As we roll along, passengers toss the bottles and wrappers out the window. Sarge tries to collect garbage in a bag, and one passenger quips “We recycle online, the train line.”

The train arrives in Santa Clara about 6 am and outside the station are a line of horse-drawn taxis.

It’s a 12 or so block walk, past a nice square, ring the bell at our hostal and wait, and wait, and ring and wait.

Back to the well-cared-for central square, sit down at a 24-hour hamburger stand and pay 1CUP each for a coldish glass of an orange-colored beverage. The WiFi is working, our host Alain responds and it’s back again.

The house is in great shape, the toilet and AC works and we sleep until lunch. Alain lives in the house with his mother, is renovating the one next door to expand his operations, and has four or five women employed cleaning and cooking. One makes a stew of beans, malanga(?a type of root vegetable) and smoked pork and sausage. That’s followed by a whole fish for each of us, served on top of fried potatoes along with rice and a salad. Dessert is a soft cheese and mango purée. Well worth the 12CUC.

The heat of the afternoon is avoided by napping and watching Real Madrid lose to Juventus but advance in the UEFA cup tournament on total goals scored.

The hammerıng sun subsıdes, so it’s time for a stroll over to see Che’s tomb where his resignation letter to Fidel is displayed in metal type on the wall.

Then, two strange dining experiences. The first, a stop at an ice cream parlor that drew lines earlier in the day. We sit down, learn they don’t have bottled water and bring us the only thing on the menu, small plates of ice cream. It turns out it’s a government run parlor where the public can enjoy heavily subsidized and delicious ice cream.

Next, a pizza place for an appetizer of small wedges of sliced ham called Jamon Viking and a Velveeta-type cheese wilting in the humidity before a pizza made with the same cheese atop a puffy pre-made crust.

That’s all forgiven by a stop in an exquisite hotel down the block where a tumbler of seven-year old Havana Club rum with one giant ice cube sets me back $1.50CUC.

That soothes the pain of my Yuban delusion but I’m convinced something is still out there. Pondering this, it’s off to one our main objectives, a Cuban baseball game. A 10-minute walk brings us to a sports complex with riverside barbecue grills and tables for picnicking, a few bars and restaurants, a playground and park decorated with an out-of-service fighter jet and helicopter and a large stadium.

Vendors line the parking lot in a row and the ticket lady explains the seats are one or two pesos CUP, and my CUC seem like a headache to her, so I buy a beer outside and get change. She says we can sit in the area behind home plate for foreign visitors and we plop down in the front row behind home plate.

The players are preparing for an upcoming international competition and are split into central and western teams. The Centrales jump on the Occidentales starter early and are up 5-0 after two innings. He seems to have settled down when I come back from the bathroom, which had a 55-gallon drum instead of running water because all of the faucets and the toilet tank were missing or never installed.

The game ends when a light in right field blows out with a tremendous pop and the officials decide to call the game in the sixth inning.

Walking back, I notice

the houses in Santa Clara are generally in much better shape and Alain dismisses Janet’s comments about stairwells and facades, saying people can pool their money for repair. The larger size of many Havana buildings makes me think that’s harder.

The next day, we arrange our scheduled 16-hour train ride to Santiago, where another Airbnb host awaits us. At the snack bar I discover what this country has is a good 4-cent cigar.

Government subsidies provide items that are astonishingly low-priced for foreigners: a four-cent cigar, eight-cent baseball ticket, 24-cent beer. That also helps maintain a low-cost workforce for the tourist hotels, shops and attractions that their employees will never patronize. In some ways, this seems no less bizarre than the out-of-control San Francisco real estate market that spawned Airbnb.

Unlike earlier, the station is crowded when we arrive 90 minutes early. Sarge made sure we lugged a doggy bag from lunch along with a few water bottles and napkins. I opted to see what awaited us: a tray full of sandwiches with a painted metal sign next to it reading “Pan con Puerco 123.5 g $5.00.” That turned out to be the price in Cuban pesos, not CUCs, or about 20 US cents each at the 24-1 CUP/CUC exchange rate. They were delicious, just one bit of grizzle in the moist, roast pork sandwiches served on the buns that are sold everywhere.

I go to the bathroom and on the way out a guy sitting on a chair counting bills makes a hissing sound to get my attention and says I have to pay.

“Cuanto será?”

“Depende, de donde eres?”

So, I tell him I’m from NJ but of Spanish parents. Meanwhile, a soldier/police man in khakis wanders over to see what’s going on.

“Really? I have a twin in NJ. Ok, give me something small.”

I tell him my friend has change and I go and get some.

We settle in to wait and the train before is delayed, worrying us a bit. Our train comes in on time but we have to cross the tracks behind the delayed train and step onto the platform, all while a steady rain starts to fall, blowing into our cabin through a cockeyed window we can’t fully close.

The conductor comes back a few minutes later and I ask her to let us know when we are getting close to Santa Clara, which should be about 1 a.m., according to the schedule. She tells us flatly that it will take eight hours, not four.

Underway, our burly cabin mate shows us photos of his son, his ex-wife, his current wife and her two children. Yovani says his father left in the Mariel boatlift and he hasn’t seen him since. He plans to join his wife in Florida in a year or so if all goes well. His wife talks to his father, he’s not that interested.

A vendor comes by and Yovani buys us a beverage in a bag we open with our teeth and suck out through the hole.

The kids in the next cabin are heading to a nearby city for a music festival, paying 10 pesos for their ticket, or about 40 cents, while ours cost 10 CUCs.

We fold down the seats to form the six seats into three beds of sorts. Our cabin mate warns us to push our shoes under the seat so they aren’t stolen, despite the fact two officers are patrolling constantly, and we watch lightning flash over the sugar cane.

For those who may have heard and are worried, I’m fine. I will be open soon. Thanks for your support.